Coover Regional Grantmaking

Ozark County’s Hammond Mill Camp receives funding to restore roofs covering critical spaces

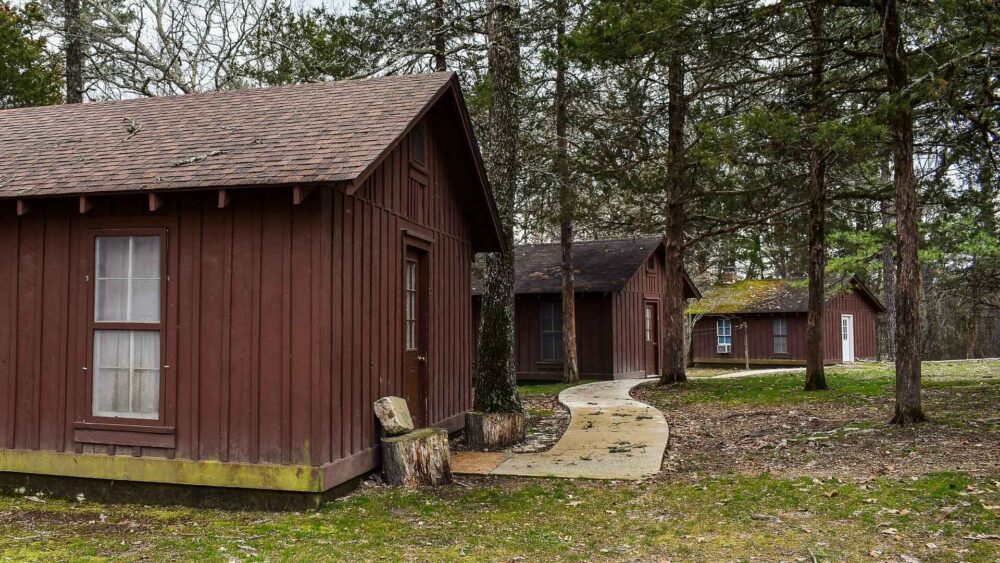

Hammond Mill Camp may be tucked away from the world, but it’s close to the hearts of generations for whom the destination is a landmark — and part of their lives.

The wooded acreage, found in rural Ozark County about 17 miles east of West Plains, has hosted decades of youth camps, family reunions and community events. For some locals, memories made in the wooded world of its own don’t end: Once attendees as children, they continue coming back for events as adults.

Yet while memories may be rich, they don’t pay for upkeep. Over time, maintenance needs at the camp have grown. As an example, the roofs covering the bath house and dining hall must be replaced. In one instance, a damaged spot is covered with bricks.

Those particular issues will soon be addressed through a nearly $25,000 grant from the Coover Charitable Foundation, administered in partnership with the Community Foundation of the Ozarks. Work on the roofing project is expected to conclude before camps begin this summer.

“I think it’s important for the youth,” says Robin Mustion, chair of the Hammond Mill Camp’s board of directors, of the camp’s purpose. “I think that (the original goal) was to provide a place where people could come and children could come and spend time safely away from the world.

Robin Mustion is chair of the Hammond Mill Camp’s board of directors.

“And, I mean, look at the distractions in the world now. You come here, you don’t have internet, which for young people is a challenge. But it’s wonderful, because then they’re focused on their camp or their families.”

Hammond Mill Camp’s legacy

It was about 90 years ago when members of the Civilian Conservation Corps Camp No. 727 constructed a series of buildings in the Mark Twain National Forest. The site was an early project for the local CCC chapter, which was part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” program to create jobs across the country.

“Besides the actual conservation of the forest lands of the United States, this project is taking care of a great army of young men who are unemployed. This work keeps them off the streets and out of pool halls and gives them more confidence in themselves and an opportunity to help themselves,” noted the Howell County Gazette in 1934.

“As soon as the camp is established and its roads, telephones and other necessary projects are completed, the men will begin cutting out diseased and poor timber growths in order that the valuable timber may have a chance to develop. Rangers will keep watch for forest fires, the dreaded menace of all forests. Observation towers are being built from which the wide range of forest can be seen.”

The camp helped men work and learn new skills. By the late 1930s, that list included automotive repair, boxing, cooking and baking, leadership training, reading, writing and road construction.

“They did a lot of historical stuff for this area and they stayed here,” says Mustion. “It’s really an interesting time when you look at what those men did.”

The end of the CCC came in 1942, as resources were desperately needed for World War II. By then, Hammond Mill Camp had already transitioned to a new life as a youth camp.

In 1941, a Springfield newspaper notes 50 underprivileged Springfield youth “who couldn’t go otherwise” were to travel to the camp. Other Ozarks newspapers also tell of 4-H members spending time at the camp early in the decade.

By the late 1940s, however, news stories reported the camp was considered for demolition. That ultimately didn’t happen: In April 1947, the Rev. Neal Jantz, a home missionary with the American Sunday School Union, transferred from Montana to West Plains and leased Hammond Mill as a Bible camp.

“Under his direction and actual work, the old buildings were renovated enough to be available for the first summer camp which was held in 1947,” notes the Springfield Daily News in 1974.

Hammond Mill Camp began in the 1930s as a Civilian Conservation Corps project. Today, it's leased from the Mark Twain National Forest to serve as a youth camp and event space.

The chapel bears Jantz’s name today, memorializing the man who worked to create the camp and lead it for at least 30 years. Eventually, leadership transitioned to an association and later a board of directors, which oversees the camp today.

“A lot of the kids couldn’t even get here, so he had a Volkswagen Beetle and he’d go to a 50-mile radius and make arrangements,” says Andy Ingalsbe, a Hammond Mill Camp board member, of a period in its history. “He’d pile them in the Volkswagen and get them here.”

The camp's role today

Hammond Mill’s Bible camps — divided by ages — have continued ever since. While they have long been a staple of the natural oasis, many other groups and gatherings regularly use the space as well.

An example is the Ozark Area Community Congress, a nature-based weekend convention, which takes place at Hammond Mill. Families, too, have long visited for events: Another example is from Mustion’s own relatives, who have gathered for an annual reunion for about 70 years.

Yet, at the heart of it all are youth. Another longtime youth camp is D.O.W. Camp, which began in the late ’60s to provide free camping for underprivileged children in Douglas, Ozark and Wright counties.

“I didn’t realize the magnitude of D.O.W. Camp, (but) I began to see it when I taught (locally),” says Mustion, who also serves on a separate board for the local camp. “I taught special ed and some of my kids would get to come. Just the experiences that they had, and then some of them came back as counselors — it’s a really cool thing.”

Even though use of Hammond Mill is open to all, Mustion explains that through the board’s lease with the Forest Service, the priority is for youth use.

“First of all, for challenged youth with disabilities or any kind of a challenge. And then it’s underprivileged. And then youth in general. So those are the top priorities, and they charge us less for those camps.”

Visiting the camp

Over its nearly nine decades, the camp has seen improvements. In the early ’60s, the desire for a long-term lease led to a nearly complete rebuild from the original CCC buildings. Boards and building materials were salvaged as much as possible, today living on through the current structures.

“To tell you what kind of a man Mr. Jantz was — there was a barracks right out in here,” says Ingalsbe. “I think everybody that used the camp got nails and a rock and straightened the nails before they went to the fire. The nails went back in.”

Today, the only original structures that remain are a cabinet holding firefighting supplies near the dining hall, and the former water tower.

Other improvements have been made with time, including the installation of air conditioning in the cabins, new sidewalks and an effort to make the camp more accessible to individuals with disabilities. But changes in use and the COVID-19 pandemic have significantly affected income in recent years, leading to critical issues.

Many of Hammond Mill Camp's buildings have been replaced over time, but are in need of updates to keep them usable for events at the facility.

The camp did receive some funding through local CARES Act grants, helping address ongoing expenses. Other needs, however, remain: Roofs, especially on the bath house and dining hall.

They are imperative fixes, as they are central to the camp’s operation.

“We’re required to meet all the Forest Service stipulations, like on the roofing. You can see what’s happened,” Mustion says, pointing to moss covering the roof of the bath house. On one section of the roof, bricks cover a patch where a tree limb fell through and was soon covered by moss.

“At one point since I’ve been here, we cleaned all of this one off, but it comes back.”

Roofs on the bathhouse and dining hall were replaced as a result of funding from the Coover Charitable Foundation. Here, one is shown prior to replacement.

Passion for the camp has led collaboration for its upkeep. A local company agreed to cover the labor for replacing the bathhouse roof, and Ingalsbe is donating its interior remodel as a service to the camp.

“They were just privacy fences,” Ingalsbe says, showing the removed doors now piled on the ground that used to divide sections of the bathrooms. “They weren’t even treated; just ‘conservation’ brown like everything else.”

Protecting what’s inside is also a priority at the dining hall, where another coat of moss covers the roof. Replacing it is crucial, as use of the building is central to the camp’s operation.

Inside, wooden tables and chairs await visitors and campers. Moments of history speak without words. Mustion walks to the fireplace at one end of the lodge-style building and shows a silver jug once used for water. Overhead, a wagon wheel and livestock yokes hang from the ceiling. Out front, beams in the wooden fence are bowed, memories left from where people sit.

“It’s just so important to keep it going,” says Mustion. “It’s a legacy that we need to keep going.”

By Kaitlyn McConnell, writer in residence for the Community Foundation of the Ozarks