CFO Stories

Howell County’s Sadie Brown Cemetery a touchstone for community connection

Restoring and rekindling links to the past

Restoring and rekindling links to the past

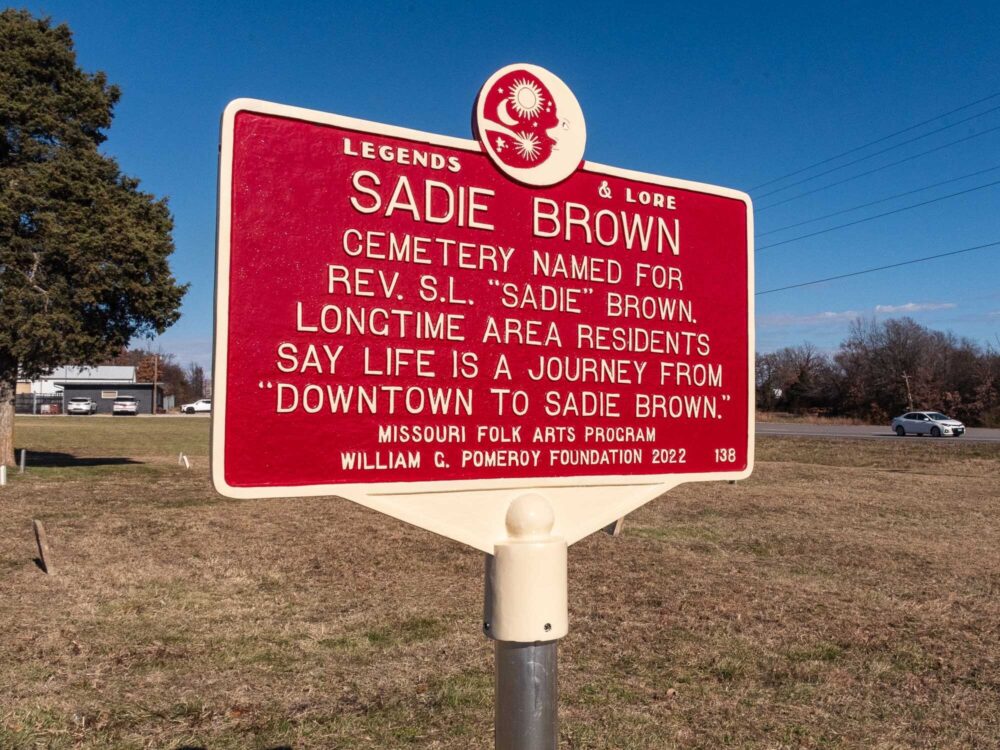

Despite traffic that constantly buzzes by, the small grassy spot at the corner of U.S. 63 and Missouri 14 feels silent. An unknown number of stories are buried beneath a couple of trees. Only a sign near a small parking lot confirms you have reached the Sadie Brown Cemetery.

It’s possible that many people who travel by don’t even know the Howell County cemetery is there, let alone of its significance: It is an historic African American site that dates to the late 1800s, containing graves of some who lived when slavery was legal in the United States.

Many who are buried there took their names and their stories to the grave. Those originally marked with fieldstones have been permanently silenced, save for shallow indentations on the ground. I’ve also heard the possibility some graves were disturbed during past road construction.

“Now, why were the graves unmarked? It’s complicated — but not really,” said Crockett Oaks III, who is leading efforts to restore the cemetery and has personal ties to the burial ground. “You’re talking about poor folks. You’re talking about slaves; some former slaves. Descendants of slaves and first-generation from slavery. Folks just didn’t have money, and although tombstones were known, they weren’t for us. They were for white people.”

In the coming months, work will begin at the sacred spot to help those individuals live again through locating and marking more than 100 graves, allowing the cemetery to continue to be used for future burials.

The efforts are made possible in part by a $22,000 Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Grant from the Community Foundation of the Ozarks. In addition to markers, funding also will help add eight benches for rest and reflection at the cemetery.

West Plains-based Heart of the Ozarks United Way officially requested the funding, which sums up its “why” in the application:

“Change will be achieved by finally marking graves and by creating a cemetery that is aesthetically on par with cemeteries that historically did not cater to minorities. No longer will the Sadie Brown Cemetery appear to be the ‘Black cemetery,’ but will be equal to all other cemeteries in Howell County.

“Descendants will have renewed confidence in their community by the groundswell of support to make the cemetery whole. With renewed direction and restoration, families who have lost confidence to be buried at the Sadie Brown Cemetery will be given back part of their family heritage, part of their history, as well as voices lost as a result of poverty and past racism.”

While the funding is necessary to make the work possible, it’s also propelled by Oaks, whose father — Crockett Oaks II — has long served as the cemetery’s caretaker, and whose ancestors are buried at Sadie Brown.

“It’s a labor of love.”

Crockett Oaks III grew up in West Plains, and recently returned to his hometown, where he serves as associate vice chancellor of business and support services for MSU-West Plains.

I recently met Oaks in his office at Missouri State University-West Plains, where he works as associate vice chancellor of business and support services. The Howell County seat is a place he knows well: It’s where generations of his family have lived and died, it’s where he grew up, and it’s where he and his wife recently returned to live.

“My great-grandmother’s parents, so it’d be my great-great-grandparents, were slaves in Arkansas, around the Imboden, Arkansas, area,” he said, referring to a town about 65 miles southeast of West Plains. “Our name — Oaks — traces back to the plantation owner in the Imboden area.

“There’s some folks down there who don’t look like me that bear my same last name.”

His connection with the cemetery spans beyond his life, and his work to educate about it began at an early age. He went to his computer and pulled up YouTube to replay a piece of the past: His teenage face came into view, telling the cemetery’s story. Back then, he shared that Sadie Brown was a widow who donated land for the cemetery.

He’s since learned more — “The whole story that I told back in ‘87 was completely wrong,” he remarked — but the interest was there, even as a young adult.

The truth of the matter was that instead of a woman, the cemetery was named for Saint Leger “Sadie” Brown, a minister who was once enslaved. He was granted 80 acres in 1891 under the federal government’s Homestead Act, and dedicated a portion of his property to be used as a Black cemetery.

It was a continuation of tradition: Even before Brown owned the property, it was used as a burial ground for Black residents as early as 1880. The land fulfilled a need in the small community, which saw an influx of minority residents to the Howell County area after the Civil War. They came for a variety of reasons, including for jobs with the railroad and in the fruit industry.

“I’ve looked at the census data and you just see after 1882, ‘83, ‘84, the numbers of African Americans in Howell County, and especially in Dry Creek Township, just began to increase relatively significantly,” said Dr. Jason McCollom, associate professor of history at MSU-West Plains. “But those numbers are never big. They’re never more than maybe one percent of Howell County’s population, but it’s a vibrant community.”

Perhaps it also felt like a place where racial tensions were less severe than other places. In several nearby counties, Blacks were simply not allowed. In later years, the town did not have a sundown law — prohibiting African Americans from being out after dark — or a racial cleansing that expelled residents. Several other Ozarks towns had these realities.

But it wasn’t a utopia.

“In West Plains, African Americans were a known entity. Often, they had been here for generations, many of them worked for prominent white families, so they were integral to the economy,” said McCollom. “But on the other hand, we don’t want to minimize this: Segregation was absolutely common. Black folks were considered second-class citizens.”

Just one example: West Plains’ Lincoln School — a small, white building where Black students attended through the 1950s — still stands to remind of a time when equal and separate were considered synonymous. It only went through the eighth grade, and with no high schools open to Black students nearby, most simply stopped their education.

West Plains' Lincoln School was a place of education for Black students through the mid-20th century.

Those differences are something Carol Silvey also sees.

Silvey has spent decades in Howell County, serving as a professor of history at MSU-West Plains and in development leadership positions with the college, the CFO and Ozarks Healthcare. She’s also devoted much time to significant community service, which includes her role as past chair of the MSU Board of Governors.

When she arrived in West Plains in the early 1960s, however, she was a high school teacher in a classroom where Black students wouldn’t have been able to be just a few years prior. There wasn’t significant visible racial conflict — but that fact created a unique challenge, she says.

“There’s really never been tension. I think the Blacks would have been better served had there been a little bit,” Silvey said. “I think tension causes people to realize there’s an issue. As it was, we treated them as individuals, not as a race. I don’t know that you develop an understanding and an appreciation of race when you’re looking at an individual.”

While it might have felt that things were “fine,” a specific example Silvey shares is a local Black woman who, in the past, regularly cooked for white families — including on holidays, leading her to postpone her own family celebrations.

Such examples perhaps contributed to a sense of stability, but not complete equality.

“I think one of the dominant reasons why racism never really impacted this community to the point of there being riots and lynchings and things of that sort is because African Americans understood the line,” Oaks said. “They understood the line as evident as the line on this notepad. And they didn’t cross it.”

When Oaks grew up, West Plains still had a thriving, tight-knit Black community.

Over time, and like many Ozarks towns, numbers have decreased as older generations have passed on and younger ones headed out to find new opportunities, just as Oaks and his brother did.

After graduating from high school, Oaks earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and worked in a variety of occupations, including as a special agent with the FBI and a police officer in Oklahoma City. For more than 33 years, he has trained for a variety of roles as an Army Reserve officer and currently holds the rank of colonel.

That work took him across the country and around the world, but family health challenges ultimately led him back to West Plains in 2021.

“For those that are still here, that sense of community is very much alive and thriving — but it’s an aging fleet,” he said. “Folks are just getting up there in age, and their offspring have moved out of the area. It was an anomaly, really, in my community for me to move back.”

Soon after he arrived, his focus fell on Sadie Brown. There were the foundational connections through his family and his father’s longtime dedication to caring for the cemetery. It grew in a new way after Dr. Dennis Lancaster, chancellor of MSU-WP, asked Oaks and McCollom to give a presentation on Sadie Brown, leading them to discover more of its history.

In the months since, Oaks’ work to recognize the area’s Black history also led him to commission “The Protector,” a large mural showing a Black woman and two children off the West Plains square. Painted by Dr. Bolaji Ogunwo of Nigeria, it’s based on artwork by the late Charles Kimberlin, a West Plains artist, and cites Isaiah 66:23: “As a mother comforts her child, so will I comfort you.”

“You have the Sadie Brown Cemetery, you have a few of the namesake streets and fields that were named; the baseball fields that were named after African Americans,” he said. “There are a few things around, but nothing, I think, that really solidifies our history and the sense of pride associated with that history.”

Oaks led the installation of "The Protector," which was created by Dr. Bolaji Ogunwo of Nigeria.

I returned to my car and pulled away from Kellett Hall, a historical, red-brick former mansion, and took my thoughts on a tour of West Plains. I stopped at the former Lincoln School, which today Oaks said is owned by the city. It reminds that history is not far in the past: At least one person who attended this school — Oaks’ father — is still alive.

It’s unclear when it closed; some schools continued operating for years after the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling on Brown v. Board of Education ended segregated schools. For older students, however, a moment of significance came quickly after the landmark ruling.

“It was a unanimous vote that the African American, high-school-aged students would be accepted in 1954,” Silvey said of a decision by the West Plains Schools Board of Education.

I pulled back onto the highway and drove out of town, headed to Sadie Brown.

When I arrived, I’m surprised and a little embarrassed: I’d driven by countless times and never realized a cemetery was there, let alone its historic significance. There are U.S. military veterans there, such as Bob Givehand and Jewell Talton — the latter who, according to Oaks, earned five Bronze Stars.

“For a person to get five Bronze Stars in a segregated military back then, it probably suggests he would have been a Congressional Medal of Honor recipient if someone really looked at it, did the research and righted the wrongs of the past.”

As I walk through the plot of grass where folks who lay never knew there’d be such a road, let alone the concept of today’s cars, I see some stones and names upon them. A few appear to be hand-carved. Others are fading. And many lives have no marker at all, hinted at only by indentations in the ground.

The Sadie Brown Cemetery is located approximately six miles north of West Plains on U.S. 63.

Once new markers are installed, it will serve the people who are buried there, as well as those who remain to see it so. But Sadie Brown has the potential to benefit more than the families with a loved one buried there: It’s a place that brings groups of people together not only for history, but also for community and creating new bonds.

After all, as the application for the grant funding put it: “The recent activities surrounding the Sadie Brown Cemetery serve as a great example of the white population and African American population of Howell County working together towards a goal that is race-centric.”

“Issues of diversity, equity and inclusion are largely invisible or dismissed in Howell County because it’s easy to deny that diversity exists in this predominantly white county. There are also no multicultural venues in the county. The Sadie Brown Cemetery therefore represents a starting point for cultural visibility.”

In some ways, it’s already working to that end.

There have been cleanup days to engage the community, including one that brought more than 30 people from different organizations together, and a research day with MSU’s Center for Archaeological Research.

In 2021, the center composed a comprehensive list of work at the site. The list included creating an outline of the cemetery’s history, the cultural research and archaeological and geophysical work necessary to find graves sites, and suggestions for joining the Black Cemetery Network.

It also recommended that the site be nominated for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places.

Even though people buried at Sadie Brown are local, the cemetery’s presence is also part of a story that is beyond Howell County.

It’s a place of note for the greater African American history in the Ozarks. In the early 1900s, numerous towns across the region saw expulsions of Black residents. That horrific reality, and smaller numbers of Black residents compared with white, results in a limited number of Black landmarks in the overall list of cultural sites across the state.

Their presence teaches, and also reminds.

I recently visited with Dr. Gary Kremer, executive director of the State Historical Society of Missouri, who spoke to the importance of preserving such places. He felt so strongly about their documentation that he personally began researching them in the 1970s.

That fact makes documentation crucial to telling the true story of the region.

“They’re important because they remind us of this significant Black presence in those communities at one time, even though there is no longer that significant Black presence anymore,” Kremer told me. “They simply remind us that African Americans lived all over the state of Missouri, not just in the urban areas or the Bootheel or the Boonslick. There was a black presence in virtually every county in Missouri.

“The Sadie Brown Cemetery is not unique, although I think it’s extremely important. It’s not unique because there were these Black communities throughout the Ozarks, which had Black cemeteries that Blacks were forced to be buried in, because they couldn’t be buried in white cemeteries. The existence of the cemetery’s documents, among other things, that there were these pockets of Black population in a part of the state that people today tend to think of as having an all-white history.

“The structures that tie people to locations in the Ozarks, if you’re African American, are few and they’re in danger,” Kremer said.

That’s one aspect the CFO grant funding helps support. The $22,000 grant will first work to restore and remember those buried there by providing grave markers, landscaping and benches at the site.

“It’s an honor to support the Heart of the Ozarks United Way’s work at the Sadie Brown Cemetery,” Bridget Dierks, vice president of programs at the CFO, told me. “In locating those who were buried at the cemetery and ensuring they are remembered for future generations, we are able to honor our Ozarks history. Being able to bring back this space for future use helps ensure families may continue to bury their loved ones together.”

The combination of those efforts, which will largely begin in early 2023, represents a moment of significance for those buried as well as residents in the present. It also allows the cemetery to be used going forward without disturbing unmarked graves.

“I guess a sense of justice and heart kicked in to want to do something,” Oaks said. “Having the ability, the means, to do something, then we should do that. It’s a way, in my mind, as a son looking at aging parents, to give them the confidence that they need to know that their resting place is going to be cared for, and let them see what the Sadie Brown Cemetery could be with a little bit of money, time and diligence.”

By Kaitlyn McConnell, writer in residence for the Community Foundation of the Ozarks